SOPHIE REINHOLD: I STARTED A JOKE

“I started a joke that started the whole world crying.”

This confession kicks off the eponymous song by alternative rock band Faith No More, a cover of the Bee Gees original from 1968. What for some is just a simple three-verse song is for others a song about “Jesus on the cross from the Devil’s point of view,” as posted on a Beegees fansite. For others, however, the song’s irony consists of a cathartic realization for both artist and audience about the consequences of a paradoxical reality: “Oh but I didn’t see that the joke was on me. And I started to cry, which started the whole world laughing.” Sophie’s exhibition walks on this exact fine line between comedy and tragedy by stripping naked the Janus-faced, ideological imagery facing the viewer as if to ask: what does it actually mean to depict something realistically? As we have learned from Brecht: “Realism (...) is art’s answer to a world torn apart by contradictions.” High up on the wall, in typical St. Petersburg manner, are picturesque scenes of characters “doing funny business” with one another. Fluctuating between abstract and figurative surfaces, with a compulsory need to represent and be recognized, they reveal humorous and striking vulgarities beyond the reach of the detail-eating eye of a peep show. Her depictions of women are drawn from 1960s Playboy comics—“porn jokes” from which some teenagers and grown-up painters, might draw inspiration from. A supposedly abstract, faceless and naked body with a flowing mane and hard nipples rides passionately on an overwhelmed green figure with terrified bug-eyes and an open mouth. Another body kneels with an empty expression and outstretched arms in front of its greedy green ass-eater: clumsy versions of H.P. Lovecraft’s “Deep Ones,” which nurtured the founding of the modern xenophobic and occasionally misogynistic horror genre.

One might think here of Jean-Luc Godard’s magnum opus Histoire(s) du cinéma (1988-1998). In the fourth episode, Fatale Beauté, Godard presents the faces of tragic women from film, photography, and painting and elevates them to the epitome of the volatile and abstract, indeed to the Albertine mystery as we know it from Proust’s novel À la recherche du temps perdu (1913–1927). The women’s faces withdraw until their dissolution or are wiped out to the point of emptiness. Here, the filmmaker, similar to the painter as monteur, thus exposes the visual semiotics and the prurient structures of viewing that dominant culture has so famously institutionalized: painting “(...) is an ideology based on men living out through their imaginations what they could not do with women.” (Godard)

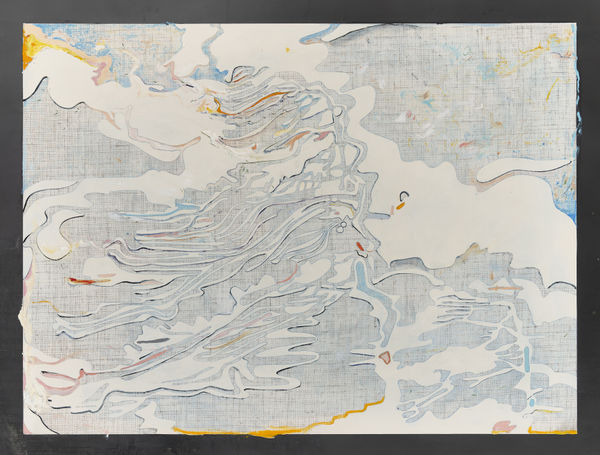

Do the pink flesh-colored surfaces represent female-read bodies consensually indulging in libidinous lusts while their faceless subjectivities are, in fact, exploited by the “voyeuristic gaze” of the viewer? Are these depictions just brainwashed essentialist projections on an innocent, abstract-colored landscape? What for some viewers might represent an objectifying affront to feminism in the “lowbrow” paintings hanging on the upper level of the gallery is, for others, a painterly reference to Matisse’s iconic Fauvism in La Tristesse du Roi (1952). Ultimately, one also encounters the half-closed eyes of the “seductive” and, at the same time, distanced gaze of the most famous nude depiction in a different painting on the wall—La Grande Odalisque (1814) by Ingres. Renowned for her elongated “abnormal” proportions, Sophie’s version of an odalisque seemingly judges our ability to recognize her. “Abnormal” is also what Sophie calls the “lower level of reality”—paintings which she places at the viewer’s eye level. Just as the masterful look of Abstraction (haters might say she mocks Paul Klee) might conceal a simple infographic or lunar calendar that was once laughed at, so it is with the dark-gray reflective graphite surfaces that seem to run deep at second glance. Filled with layers of paint by hand and then smoothed with a trowel, surfaces here were modeled, polished, and created with bitumen. Ground marble and graphite powder change shifts and with the help of other hands: a sort of alchemy exposed on the surface. However, in the end, these polished reflective surfaces always leak as Sophie’s raw, gestural, subjective marks are inextinguishable, complicating mere static representation: they settle down like deep scratches on a shiny metal car door that cannot be painted over. Instead, surfaces here constantly perform and visualize the impending but failing process of flattening—refusing the allure of being smoothed in the style of Orwellian doublespeak and in favor of a sharpening of the lazy eye, which here constantly undergoes a kind of “vision test.”

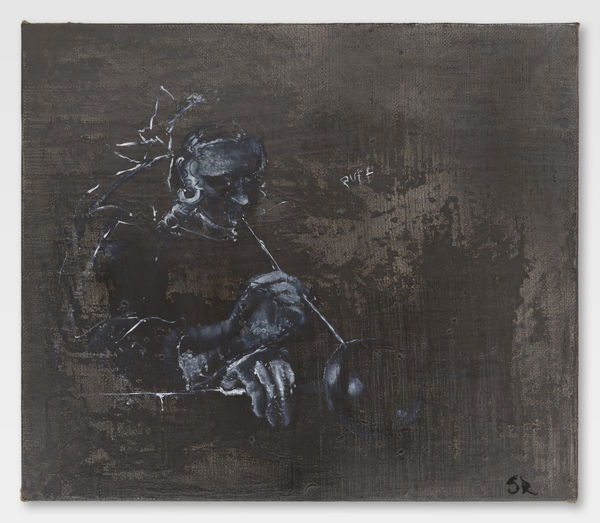

“Puff”—a crude slang term in German for a place where sexual services are offered—a black painting reads, like an easily-overlooked cheeky scrawl in a generic public toilet. Next to it, a figure with delicate outlines performs a “blow job” of a different kind: namely, a craftsman blows a soap bubble that threatens to burst, as if one could already anticipate its popping sound. Puff. – Press Release by Elisa R. Linn

-

-

The Experience of a faceless Moment/I, 2024, oil, bitumen and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 150 cm | 70.9 x 59 in.

The Experience of a faceless Moment/I, 2024, oil, bitumen and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 150 cm | 70.9 x 59 in. -

Detail, The Experience of a faceless Moment/I, 2024

Detail, The Experience of a faceless Moment/I, 2024 -

-

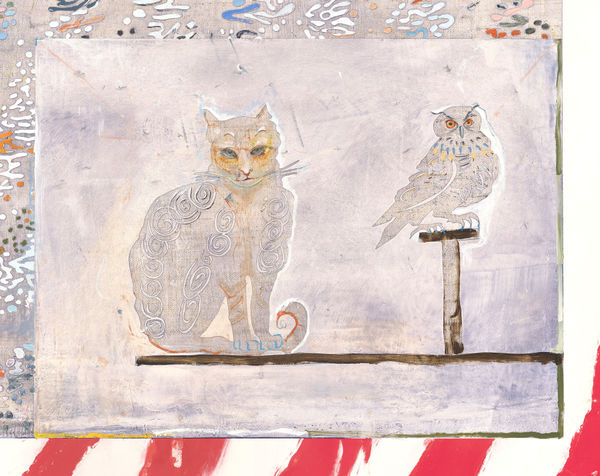

The Baron and his Moral/I, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in.

The Baron and his Moral/I, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in. -

-

The Experience of a faceless Moment/II, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 150 cm | 70.9 x 59 in.

The Experience of a faceless Moment/II, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 150 cm | 70.9 x 59 in. -

Detail, The Experience of a faceless Moment/II, 2024

Detail, The Experience of a faceless Moment/II, 2024 -

The Baron and his Moral/II, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in.

The Baron and his Moral/II, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in. -

-

Let go and stop lying…, 2024, oil on graphite and marble powder on jute, 180 x 215 cm | 70.9 x 84.6 in.

-

Detail, Let go and stop lying…, 2024

Detail, Let go and stop lying…, 2024 -

The Baron and his Moral/III, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in.

The Baron and his Moral/III, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in. -

-

-

-

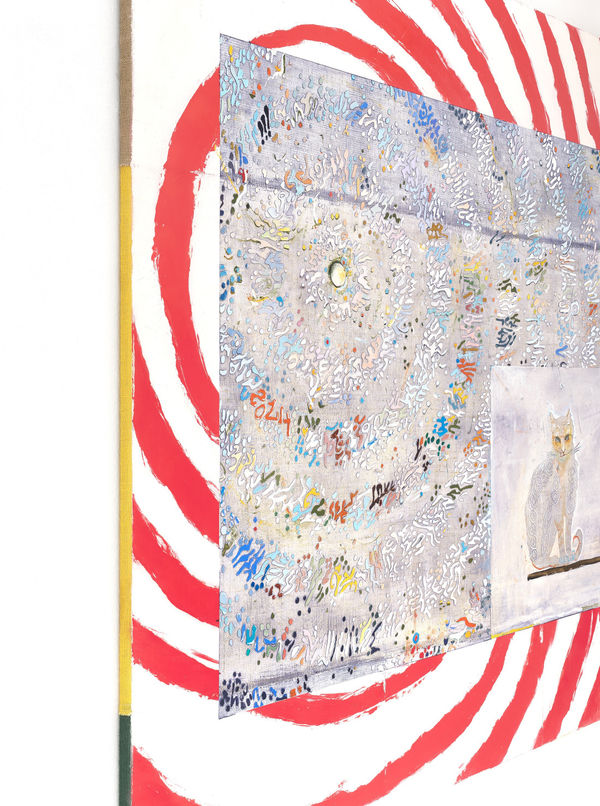

Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 215 cm | 70.9 x 84.6 in.

-

Detail, Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024

Detail, Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024 -

Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 215 cm | 70.9 x 84.6 in.

Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 180 x 215 cm | 70.9 x 84.6 in. -

Detail, Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024

Detail, Seduction of simultaneous participation, 2024 -

-

Puff, 2024, Oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 60 x 70 cm | 23.6 x 27.6 in.

Puff, 2024, Oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 60 x 70 cm | 23.6 x 27.6 in. -

Puff, 2024, Oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 60 x 70 cm | 23.6 x 27.6 in.

-

The Baron and his Moral/HER, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in.

The Baron and his Moral/HER, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in. -

The Baron and his Moral/HER, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in.

The Baron and his Moral/HER, 2024, oil and pigmented marble powder on jute, 130 x 130 cm | 51.2 x 51.2 in. -

A-T_O:P+I/E, 2024, Oil and pigmented marble dust on jute, 160 x 180 cm | 63 x 70.9 in.

-

Detail, A-T_O:P+I/E, 2024

Detail, A-T_O:P+I/E, 2024